If you’ve spent any time on social media in the last few weeks, or pretty much just spoken to anybody, then I am sure you will have heard the chorus of “I can’t wait for 2016 to be over!” “Worst year ever!” “2017 can’t surely be worse?!” and so on. It was only a few years ago, back in 2012, that many people were convinced (jokingly or not) that the world was going to end after a supposed Mayan prediction.

As with any time period, people who lived in the medieval and early modern period did not know for certain that we would be sitting here hundreds of years later, and so, too, were periodically consumed with the idea of an imminent apocalypse. No surprise, either, when the Church liked to emphasise God’s wrath on sinners and the importance of preserving your soul for the inevitable second coming of Jesus and the end of the world. In medieval texts, the foretelling power of natural events, particularly celestial, are often emphasised. Chroniclers and writers of annals would note down passing comets, eclipses, and other portents, along with the stories they were recording. Often these were suggested to have been a sign which then predicted a later event the writer recorded – the death of a King, a great loss in battle, a natural disaster.

It is no surprise, then, that celestial events were sometimes interpreted as apocalyptic. In 1524, there was a planetary alignment where all five known planets were going to gather closely together in the night sky – as close as the width of a hand. This was to occur in late February to early March, under Pisces. In 1499, a man named Johannes Stoffler wrote about the upcoming movement of the planets, saying:

“For in the month of February will occur twenty conjunctions, small, mean and great, of which sixteen will occupy a watery sign, signifying to well nigh the whole world, climates, kingdoms, provinces, estates, dignitaries, brutes, beasts of the sea, and to all dweller on earth indubitable mutation, variation and alternation such as we have scarce perceived form many centuries from historiographers and our elders. Lift up your heads, therefore, ye Christian men” (from History of the Apocalypse, Catalin Negru)

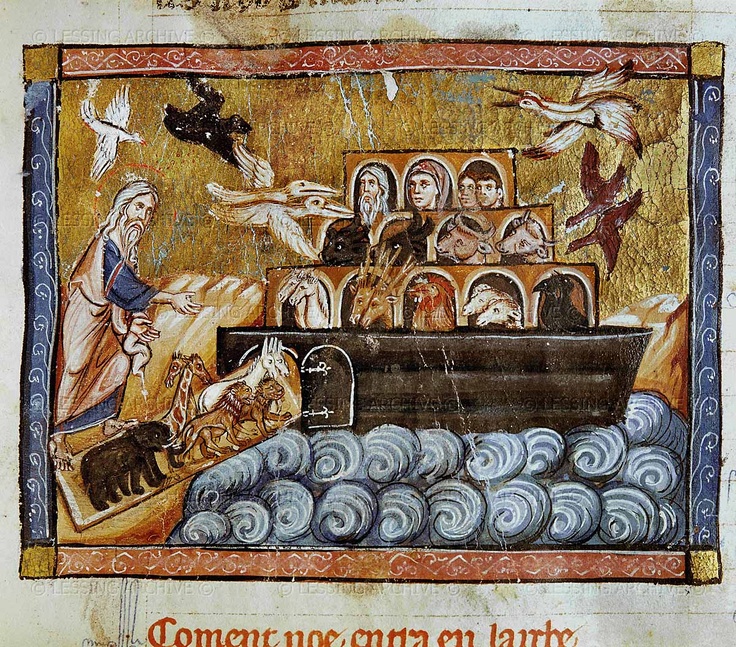

This writing then caused a rumour to abound in the West that a second universal flood (the first being the Biblical flood with Noah) was going to take place. As with all predictions of the ending of the world, there were many who scoffed at the idea – religious men highlighted that it violated God’s covenant with Noah, whilst others simply laughed at the unreliability of astrological predictions (which, even throughout the medieval period, was polemic on whether it was an accurate science or not). Many people did take the predictions seriously, however; it was said that floods would hit London on the 1st of February, and 20,000 people abandoned their homes in fear – a huge amount of people at this time.

Elsewhere in Europe, a Count named Von Iggleheim built a three-storey ark on the Rhine. This only amplified the fear amongst the common people about the rumours of a flood, and when it began to rain on the morning of the 1st of February, the crowd panicked. They rushed onto the docks to grab any buoyant object, and the resulting stampede caused hundreds of people to die through drowning or trampling. The Count, in fear, closed the door of his ark, but people climbed into the ark, threw him out, and stoned him.

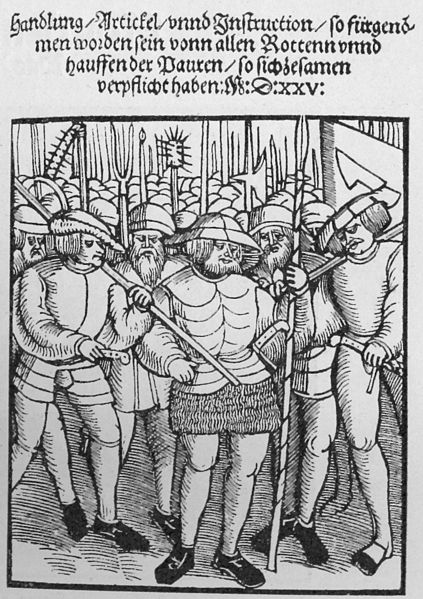

The following year in Germany, another apocalyptic prediction led to widespread slaughter of the peasantry. A man called Thomas Müntzer, who became a priest in 1514 and was initially a follower of Martin Luther’s criticisms against the Catholic Church, soon became more radicalised than Luther. By 1520, he began to believe that the Church reform movement was apocalyptic in nature, and in 1523 he had managed to get a position as a priest in Saxony. His preaching became incredibly popular, and he supposedly attracted 2,000 people from nearby areas to listen to his sermons every Sunday. In July, 1524, before the Electoral Duke Johann, Müntzer preached his “Sermon before the Princes” where he warned the princes that they should join his reforms or face the wrath of God:

“What a pretty spectacle we have before us now – all the eels and snakes coupling together immorally in one great heap. The priests and all the evil clerics are the snakes…and the secular lords and rulers are the eels… My revered rulers of Saxony…seek without delay the righteousness of God and take up the cause of the gospel boldly” (from Wikipedia)

In March, 1525, Müntzer formed the ‘Eternal League of God’, an armed militia to usher in the apocalypse. In May, his army clashed with the army of the princes of Germany with bloody results: barely a soldier was killed, but 6,000 peasant rebels were slaughtered. More rebels were later executed. Müntzer was captured, tortured, and executed.

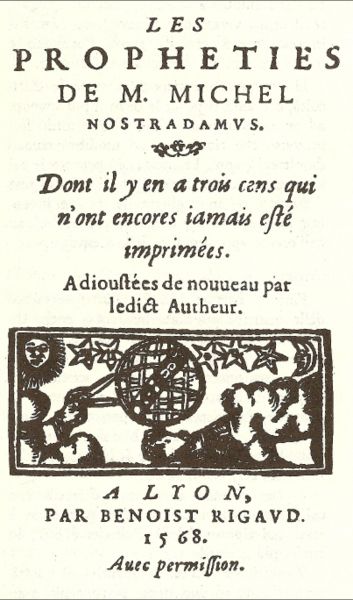

To end, I must of course include potentially the most famous apocalyptic predictor, Nostradamus. He was a French physician whom published his first edition of his collection of prophecies in 1555. Nostradamus was a learned man who went at the age of 15 to the University of Avignon. However, he had to leave after a year due to an outbreak of plague which closed the University. He then travelled the countryside for 8 years from 1521 to research herbal remedies and returned to University, this time at Montpellier, in 1529. He was expelled after it was discovered he had been an apothecary, a manual trade which was banned from University goers. Perhaps influenced by the outbreak of plague which caused him to leave Avignon, he seems to have focused on trying to cure plague, releasing a rose pill that purportedly protected against the disease. From the mid-1540s, he tried to help battle outbreaks of the disease across France. By 1550, however, he had moved his interests away from medicine and towards the occult.

Enjoying this blog post? Buy me a hot chocolate!

Consider donating the cost of a hot chocolate to me, so I can continue to write and run Just History Posts.

£3.50

From 1550 onwards, Nostradamus wrote an almanac annually which, altogether, are known to have contained at least 6,338 prophecies. His most famous prophecies came from his book, Les Propheties, published in three instalments. Whilst many thought Nostradamus was a fake, a servant of the devil, or simply insane, others took him seriously. Catherine de Medici, wife of King Henry II of France, was one of his greatest admirers. After reading his almanacs for 1555, which hinted at unnamed threats to the royal family, she summoned him to Paris to explain them and to draw up horoscopes for her children. Initially, he feared for his life, but by the time of his death in 1566, Queen Catherine had made him Counsellor and Physician-in-Ordinary to her son, the young King Charles IX of France.

Much of the content of Les Propheties focused on disasters, wars, floods, battles, and such. Perhaps partly as part of his worry that he could be prosecuted for heresy or treason, he wrote his prophecies in multiple languages including an ancient form of French worded so ambiguously that it could be interpreted to mean almost anything a reader desired. Perhaps this explains his prophecies’ enduring appeal. Nostradamus has been credited with predicting numerous events in world history, from the Great Fire of London, the rise of Napoleon and Adolf Hitler, to the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center. This credit always seems to be applied in hindsight, making the prophecies fit events, and no Nostradamus prophecy is known to have been interpreted as predicting a specific event before it occurred, other than in vague, general terms that could equally apply to any number of other events. In fact, to return to the beginning of the post and anxieties that people hold for what 2017 will bring, just two days ago The Express published an article about Nostradamus’ predictions for 2017.

Clearly, if that is to believed, we are in for another wild year! None of us know what 2017 will hold in store (unless any real-life seers are reading this) but what we do know is that worries about what the end of one year and the beginning of another will bring is as old as we are.

Previous Blog Post: Have Yourself a Merry Little (Medieval) Christmas

List of Blog Posts: here Blog Homepage: here

Buy my books via the pictures below! Or why not check out our shop?

Follow us:

Great post…Not necessary the most upbeat one out there but highly informative. Thanks for putting everything in perspective. Happy 2017!

LikeLike

Hah yes it took a slightly morbid turn! But glad you enjoyed it anyway! Happy New Year!

LikeLiked by 1 person